This Thursday, families across New England will sit down at their dining tables to celebrate Thanksgiving and mark the beginning of the holiday season. Some will have spent all day cooking; others will have fought traffic and airline cues to make it to their loved ones, completely unaware that a somber anniversary is marked each November 27—that 127 years ago to the day, the steamship Portland was fighting for its life in the tar-black waters of Massachusetts Bay with 200 people trapped onboard. Thanksgiving of 2025 shares a calendar box with an event that was so tragically complete in its devastation, it has been dubbed the “Titanic of New England.”

November 26, 1898

The air in Boston, Massachusetts was biting. It was the kind of day that would make you instinctively pull your coat tighter against the chill, or pause after stepping outside, considering whether or not you should go back for your gloves. The skies above the city were clear, but the wind was cold and brisk. The United States Weather Bureau had reported, “For Boston and vicinity—snow tonight and Sunday morning, followed by clearing and much colder weather; winds coming easterly, increasing in force, and shifting to northwest.”

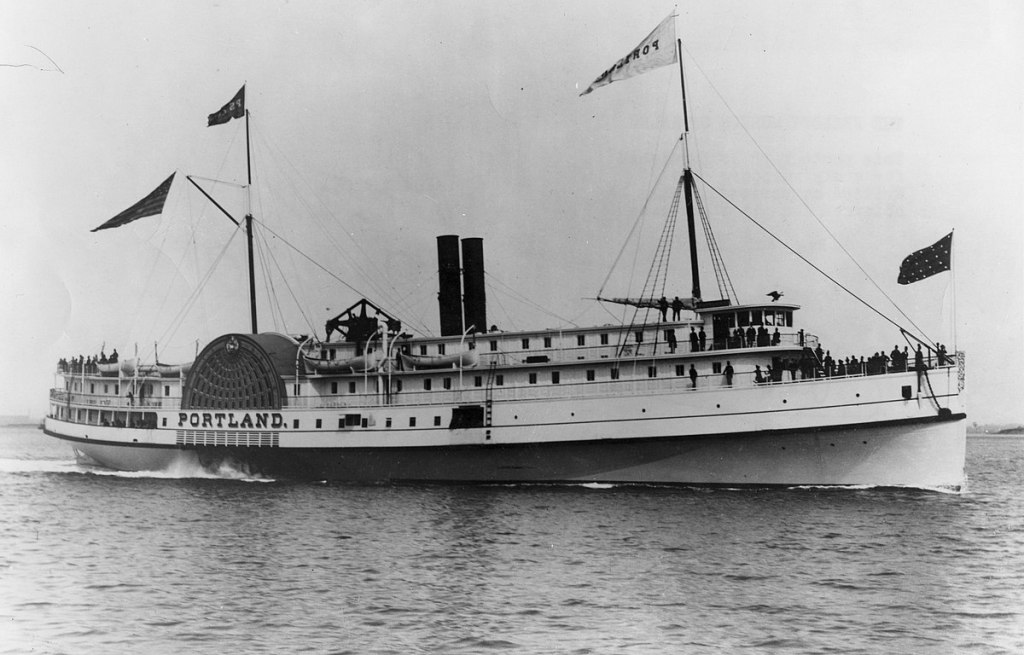

It was a late autumn Saturday in 1898; the first weekend after Thanksgiving, which fell on November 24 that year. Straining at her ropes alongside the Boston wharf sat the SS Portland, rising up all gleaming white and blunt nosed, with two iron funnels that stood sentinel, side by side, over her polished decks. Below her crowded a traveling public waiting to board the last boat north to Portland, Maine. “Some were traveling from as far away as New York, or Philadelphia.” the New England Historical Society states.

In their hands they clutched carpet bags, leather-handled suitcases, and hat boxes. Others cradled shop parcels wrapped in brown paper or bags embossed with department store logos—their Christmas shopping. Thanksgiving had been wonderful, and with Monday approaching, they were eager to board a ship that had, in her nine years of service, built a reputation for luxurious and reliable overnight transportation that was never late.

The SS Portland

The Portland, according to the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, had been built in 1889 by the New England Shipbuilding Company in Bath, Maine. Her 291 foot (88.7 meter) hull was made of wood, and she was 65 feet (19.8 meters) wide at her widest point. She was powered by a “walking beam” engine which turned her two massive paddle wheels, one on each side. Capable of carrying upwards to 800 people in comfort, she was the pride of the Portland to Boston route.

The Cape Cod Maritime Museum tells us that on the night that she sailed for the city of her namesake, a storm was sweeping across the great lakes on a collision course with another coming up from the Gulf of Mexico. The converging of these storms would create one so massive it was said to be “unlike any in living memory.” Sailing master Joseph Kemp in Boston said it was “the greasiest evening you ever saw.”

According to the Portland Press Herald, the captain of the Portland was Hollis Blanchard of Searsport, Maine. A longtime veteran of the sea and employee of the line, he would command her that night. The New England Historical Society states that Blanchard was aware of one of the impending storms, and he made a phone call to the captain of the Portland’s sister ship, the Bay State, saying he thought he could beat the storm back to Maine. The general manager of the line ordered the ship to be held until 9:00PM to see how the weather would develop.

While passengers continued to board, a man named Gott from Brooklin, Maine witnessed the Portland’s pet cat “leaving the steamer, taking her kittens down the gangway one by one.” Gott took the message as a warning and got off the ship before it set sail. When 7:00PM came, the scheduled hour of departure, Captain Blanchard, either having not received the message to hold the ship or choosing to ignore it, ordered the lines to cast off. The New England Historical Society says the ship left “before the sudden violent outburst of wind and snow” … and saluted the steamships “Kennebec and then the Mount Desert as she steamed out of Boston Harbor.”

The Portland Gale

That evening, the two storms collided over the coast. The Fishermen’s Voice wrote in a 2010 article, “the pilot boat Columbia” was “thrown from the water and smashed into a house in Scituate, Massachusetts.” An eyewitness wrote after the storm, “Millis Brigg’s house has sailed over to ‘Cut River.’ … the roads are full of great rocks and wreckage of all kinds, lobster traps, boats and furniture.” The Cape Cod Maritime Museum says, “by midnight, temperatures plummeted to 0°F and 40 inches of snow fell.” These were the conditions Captain Blanchard unknowingly sailed the Portland into.

She was seen several times that night fighting against the storm. “Several schooners caught sight of the Portland near Thatcher’s Island off Gloucester,” and “at 11:45PM, the schooner Edgar Randall nearly collided with a badly damaged steamship running without lights. During a lull in the storm, … the schooner Ruth M. Martin spotted Portland off Highland Light in North Truro,” states the New England Historical Society. The Portland and her 200 passengers and crew had survived the night, but they would not survive the gale.

It is believed that she might have foundered around 9:00AM that morning, because “the watches recovered with the bodies stopped between 9 and 10:00AM” says New England Lighthouse Stories. The New England Historical Society wrote that the evening after the Portland set sail, “bodies began to wash ashore around 7pm on Sunday. … No one knows exactly what happened. Some think she rammed another vessel. Some think the Portland Gale swept off her superstructure and she sank like a stone.” The same source states that a “Boston Herald reporter … got part of a telegram from Truro, which convinced him the Portland had sunk.” The reporter “went as far as he could, but the storm had washed out coastal railroad tracks. He continued on foot, horseback, and then train to Boston, where he filed the story on Tuesday and alerted the world to the Portland disaster.”

November 27, 1898

The world was startled awake by the storm, the “Portland Gale,” as it was called because of the lost ship and all who were onboard her. Indeed, a newspaper in California, the San Francisco Call published on November 30 a headline that read, “Steamship Dashed to Pieces.” The New England Historical Society states the storm finally broke 34 hours later, on November 28. The Provincetown Advocate wrote, “Afterward, lumber, wharf pilings, and planks from the wharves … writhed like snakes as if the surf tossed them.”

Nobody knows exactly how many people were lost onboard the Portland. According to the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, there were roughly 200 onboard, but the only passenger list went down with the ship. They go on to say, “the crew of the ship included 19 African American members of Portland’s Abyssinian Meeting House. This human loss was a contributing factor in the closing of that church several years later and dealt a significant blow to Portland’s Black community.” New England Horror Files published in a documentary that “roughly 400 people died in the Portland Gale of 1898, half of which were onboard the SS Portland.”

Today, she rests upright beneath the surface of the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, a protected site that is not officially disclosed. She is strewn with fishing nets, but her remarkably intact hull keeps silent guard over the nearly forgotten story that occurred 127 Novembers ago. This Thanksgiving, as we gather to celebrate life’s blessings with our most cherished family and friends, while wind whistles past the windows and the fire warms the hearth, let us not forget the legacy that 200 people left behind—that the drive to return home, even in the darkest hours—will be forever etched in the fabric of humanity.

Categories: Uncategorized